Worst cast scenario, the script that the writer has crafted, tortured over, and edited many times over many months of work is thrown out completely. As speaker Susan O'Connor at GDC 2013 said, "Writers live in earthquake country." Projects are often nixed altogether and the writer is obligated, presumably by contract, not to reveal this abandoned story and not to share it in any way with anyone else. The masterpiece inside the writer's head stays there until it's sent to the grave.

The other, more likely scenario is that the script is chopped up by the design team, with parts moved, edited, rearranged, expanded, or deleted. This is all a part of the process, though, as the writing team meets with creative directors, mission designers, and level designers to improve upon the material. They might even need to convince businesspeople of their ideas, defending diversity in ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation to the existing cast of characters. Writers need to balance the inflexibility that channels their belief in the script's core message and plot structure with the required modesty and open-mindedness that allows them to accept other opinions and let go of artistic dictatorship. If a scene or character just doesn't work with the core mechanics of the game, it needs to be ready for the recycle bin.

Game writers learn to relinquish, as gut-wrenching as it might feel, as if someone is chipping away at their very soul, the idea of singular authorship to the entire team and make changes based on budget constraints, time constraints, and incompatibility with the gameplay. In this way, being a video game writer is not far from being a writer on a sketch-based comedy show on television. The main exception of course is that weekly, perhaps daily, cycle of a televized series doesn't compare to the much longer average of a two-year cycle for a video game.

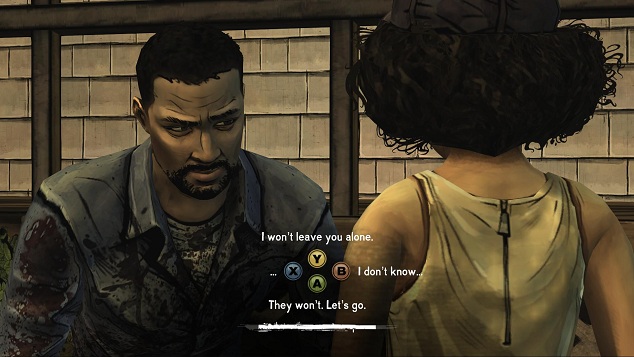

Despite the inevitable cuts, what the game writer needs to keep in mind, Susan O'Connor advises, is not the specifics of any particular scene, but the emotional journey of the protagonist. As long as that remains intact, any number of edits ultimately still serves the central message of the game, hopefully for the better.

That, in summary, is usually the best-case scenario, under the assumption that the writer or "narrative designer," a relatively new position and title in video game design studios today, is a part of the process from the very beginning. Many times, to their chagrin, writers are hired at the worst possible phase in the development cycle: the production. By then, many of the cut-scenes have already been motion-captured and finished, most of the dialogue has been written, and the core gameplay has been more or less set in stone.

Here, the only legitimate response by the writer is "What the hell, guys? What exactly have I been hired to do?!" At this point, the writer may even need to explain that game narratives don't need to be linear or be even conveyed through text, that their job is far more than being hired to write a bunch of dialogue. But any sections of the game that make absolutely no sense narratively or are found counter to the characters and the gameplay most likely have to stay just where they are. Building entirely new assets, even edited ones, would take months to complete, time and money that the studio doesn't have.

As much as the writers should have been brought in during the conceptual or pre-production phases to help mold the game's world and its central themes, they have to bite their tongue. Even if all they can do is tweak levels and mission objectives here and there, maybe get better performances out of voice actors, for the good of the team, that's what must be done.

Luckily, game writers and narrative designers have become more prominent and more necessary to the design process over the last five years, and developers recognize that for video games to become "next-gen," the narratives and storyworlds of their medium need to evolve. The mere inclusion of the Game Narrative Summit for the first time at this year's Game Developer Conference attests to this.

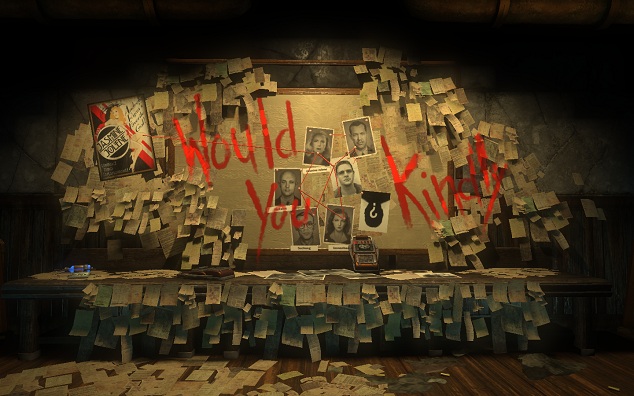

With creative lead writers/designers, like Ken Levine, Tim Schafer, and Todd Howard (just to name a few), at the helm of their studios, the future of video game storytelling is brighter than it's ever been. As the demographics of game audiences have become older and wiser, and the construction of storyworlds have become more complex and realistic, gamers have come to expect grand narrative experiences worth the premium price of $60, amidst the sea of cheaper mobile, downloadable, and online titles. Video game writers, now more than ever, are the underdogs worth rooting for. They are the heroes who have the power to change the video game industry forever—and we should let them.